“I have tried to impress upon our people … that, while our Union meetings are all in the right direction, and well enough for the present, they will not be worth the paper upon which their resolutions are written unless we can overthrow political Abolitionism at the polls, and repeal the unconstitutional and obnoxious laws which in the cause of “personal liberty” have been placed upon our statute-books.”

– Franklin Pierce in a letter to Jefferson Davis, January 6, 1860.

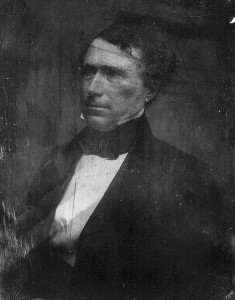

PRESIDENT FRANKLIN PIERCE

When Franklin Pierce learned the nation had elected him as President he likely did not imagine the next decade would begin with a tragic death in Andover and end with him being denounced by a best-selling Andover author as an “arch-traitor” to his country. Born in nearby Hillsborough, New Hampshire in 1804, he graduated from Bowdoin College and, after studying law, embarked on a political career following in the footsteps of his Revolutionary War veteran and New Hampshire Governor father. Shortly after his election as a Democratic state representative, the New Hampshire Legislature elected Franklin as the Speaker of the House, the youngest Speaker to serve to that point. In 1833, he gained election as a U.S. Congressman and by 1837 Franklin Pierce had become the then youngest serving U.S. Senator.

Just as Pierce’s political future looked brilliant, adversity began to darken his personal life. While a Congressman, Pierce married Jane Means Appleton, the daughter of a former President of Bowdoin, sister-in-law of one of Pierce’s college professors, and the opposite of Pierce in many ways. While Franklin was outgoing, gregarious and a rising star in government, Jane was reclusive, sickly and detested Washington. Legend has it they left for a honeymoon in Washington D.C. a mere 30 minutes after their wedding only to have Jane return to New Hampshire within the year. Within two years of their marriage, the Pierces’ had their first child, Franklin Jr. who died three days after birth. By 1841, Franklin and Jane had two more children, and he resigned from the U.S. Senate to attend to a thriving legal practice and be with his family in New Hampshire. Unfortunately for the Pierces, their second son, Frank, died of typhus in 1843.

When war broke out with Mexico in 1846, Pierce immediately volunteered for military service, and was quickly promoted to the rank of Brigadier General, serving under General Winfield Scott. Despite suffering a debilitating knee injury in Mexico, Pierce refused to leave the front lines and participated in the war’s final battle until he fainted from pain, an incident his political opponents would use against him in the future. After the war’s end, Pierce returned to New Hampshire, Jane and his remaining child, Benjamin, in December of 1847. In addition to having a successful law practice, Pierce remained active in New Hampshire and Democratic politics which eventually led to his nomination as the Democratic Party Candidate for President in 1852 against his former commander, Whig Party Candidate Winfield Scott. Due in large part to the national strength of the Democratic Party, and despite Whig allegations that Pierce was a cowardly alcoholic, on November 2, 1852 Franklin Pierce was elected the 14th President of the United States.

What should have been a triumphant time for the Pierces quickly turned tragic. After spending the holidays in Andover with Jane’s sister and brother-in-law, then President-elect Pierce, Jane and their son Benjamin left Andover by train for Concord on January 6, 1853. The trip was to be their last before they left for Washington and his Inauguration, but less than a mile from the station, the train derailed; tumbled down an embankment; and young Benjamin suffered a horrific injury to his head which both Franklin and his wife unfortunately witnessed. Benjamin Franklin, the only surviving child of the Pierces’ had died. His death would haunt Jane for the rest of her days, and she blamed her son’s death on her husband’s ambition for higher office.

Pierce’s Presidency quickly became mired in controversy. While the Compromise of 1850 seemingly had settled the slavery question and promised a time of peace for the country, his administration’s attempt to wrest Cuba from Spain and purchase of present day southern New Mexico and Arizona raised the ire of abolitionists who viewed these acts as attempts to extend slavery. Early in 1854, Pierce further fanned the flames of sectional strife when he enforced the Fugitive Slave Act by ordering U.S. Marines into Boston and a U.S. Navy ship to transport a captured slave, Anthony Burns, back to his former owner in Virginia. In the same year, Franklin Pierce signed into law the Kansas-Nebraska Act which effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820; left the issue of slavery’s western expansion open to popular sovereignty; and led to “Bleeding Kansas.” Pierce’s handling of the affair left a great deal to be desired. He ignored claims by abolitionists that voter fraud had led to the installment of a pro-slavery government in Kansas; he removed the anti-slavery Territorial Governor he had earlier appointed; and he threatened military action if anti-slavery forces did not acquiesce. In short, the issue of slavery crippled Pierce’s administration, and his own party chose not to re-nominate him in 1856.

During his Presidency, Jane Pierce chose to escape Washington often to stay with her sister and brother in law, Mary and John Aiken, at 48 Central Street in Andover, where Benjamin’s funeral services had been held in 1853. As a result, then President Pierce would visit Andover so often the home became known as the “Summer White House.” Even after his Presidency, the Pierces continued to visit Andover as demonstrated in the “The Record of Andover During the Rebellion” which notes the attendance of “Ex-President Franklin Pierce” at exercises to commemorate a large banner given by “members of Phillips Academy” to the Andover Company on June 22, 1861. Pierce’s ties to Andover did not end there, however.

In response to a July 4, 1863 speech critical of Abraham Lincoln and the public revelation two months later in 1863 that Pierce had complained in writing to Jefferson Davis in 1860 about the “madness of Northern abolitionism,” Andover resident and abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe condemned Franklin Pierce as “that arch-traitor.” She was not alone. In 1863 and thereafter, Pierce was roundly criticized in the North for his anti-abolitionist sentiments and for his friendship with Jefferson Davis to whom Pierce had remained personally loyal. Sadly, three months after Pierce’s correspondence with Jefferson Davis had been exposed, Jane Pierce died in Andover on December 22, 1863. As was the case for so many Americans in this era, Pierce’s life, once so promising, had been devastated by personal tragedy and ravaged by the dispute over slavery and the Civil War.